Regeneration Generation (in progress)

In the ongoing project Regeneration Generation, Christian van der Kooy intends to portray what constitutes a critical cultural infrastructure, and how much impact the full-scale Russian invasion has on the cultural development and manifestation within Ukrainian society.

In search along the frontline city of Kharkiv, van der Kooy got acquainted with the local artistic community through a variety of social and cultural initiatives.

Despite trauma and daily Russian destruction, these culture-makers; artists, poets, actors and musicians hold on to the desire to create and organise, without which it is impossible to live. Through photography, text and interviews Christian aims to chronicle their bootstrapping creation.

In search along the frontline city of Kharkiv, van der Kooy got acquainted with the local artistic community through a variety of social and cultural initiatives.

Despite trauma and daily Russian destruction, these culture-makers; artists, poets, actors and musicians hold on to the desire to create and organise, without which it is impossible to live. Through photography, text and interviews Christian aims to chronicle their bootstrapping creation.

It is his believe that in the time when Russia is committing genocide to annihilate Ukrainian identity, it is vitally important to recognise that Ukraine’s considerable source of strength is their thriving culture.

He is deeply affected to see how Ukrainians, despite generations of historical and cultural erasure, manage to preserve their memory and fierce energy to challenge their thirst for a free and conscious life. Van der Kooy hopes Regeneration Generation will serve as a catalyst for redefining and decolonizing the knowledge Europeans still have about Ukrainian culture.

![Artist Daria Kolo @blindeslover and Illustrator Roman Yermilov @hornless_faun, wearing a cast around his neck of a doll face left behind in the Chernobyl disaster.]()

He is deeply affected to see how Ukrainians, despite generations of historical and cultural erasure, manage to preserve their memory and fierce energy to challenge their thirst for a free and conscious life. Van der Kooy hopes Regeneration Generation will serve as a catalyst for redefining and decolonizing the knowledge Europeans still have about Ukrainian culture.

Regeneration Generation

essay by Ihor Sukhorukhov

It is impossible to talk about complex things without metaphors. My metaphor for the state of the Ukrainian culture are the stumps of trees, after they’ve fallen or been cut down, from which sprouts begin te grow.

The famous and fertile Ukrainian black soil (chornozem in Ukrainian) is a natural resource that, in theory, might have created conditions for the Indigenous people’s prosperity but led to the opposite consequences, instead of the wealth of locals — colonization and exploitation by stronger neighbors.

This exploitation carries with it depleted lands and cut centuries-old oaks. Resource extraction leads to the exhaustion of the environment and its irreversible changes.

A colonization is not interested in the future of that particular territory; the resources go to the metropolis.

To use the resource now, it is necessary to clear the land from its past: people’s memories and trees that can live a long time and be silent witnesses of the local history and sacred life. Trees carry the memory of forests; steppes are not just the absence of something. Steppes carry the memory of past generations in their bellies, externally covered with tempting pastures and fresh arable land.

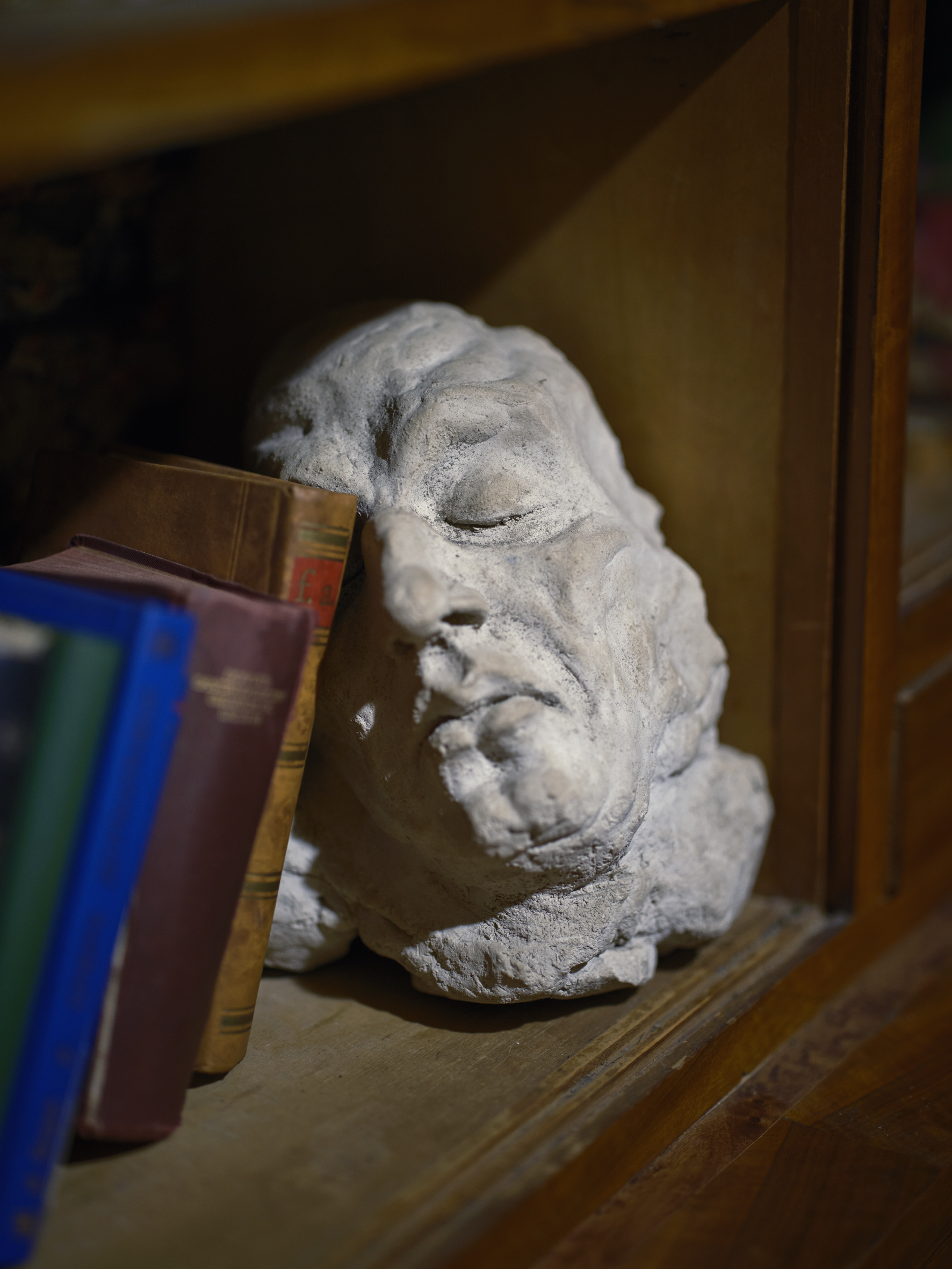

This leads to constant erasure of material and immaterial heritage. So, every third Ukrainian generation faces the necessity of archaeology: to dig the knowledge of the generations before them. Every second generation finds itself in the timelessness of survival. This third generation, which should become a formed product of the life of close ancestors, must reconstruct the reality of the past generations through archaeological practices. The natural transfer of the heritage is broken. Grandchildren barely know the complete stories of their grandparents because many things are silenced, memories are repressed or are false. There is almost no chance that significant material heritage is transferred through generations. Artifacts of the common culture are destroyed, damaged, hidden, stolen, lost; especially in cities like Kharkiv.

New generations have to collect fragments of texts, search for stucco under layers of wallpaper, exhume mass graves and abandoned graves, and collect bricks to imagine what they were part of. They try to find connections that are lost in the material but not lost in the collective memory.

Yes, this memory resembles a landfill, but the attentive gaze of a researcher, who examines the material with an archaeologist’s optics, can recreate an entire ecosystem from several dinosaur bones. There is a legend that when the iconic constructivist masterpiece Derzhprom was built in Kharkiv in the 1920s, they found a mammoth bone.

essay by Ihor Sukhorukhov

It is impossible to talk about complex things without metaphors. My metaphor for the state of the Ukrainian culture are the stumps of trees, after they’ve fallen or been cut down, from which sprouts begin te grow.

The famous and fertile Ukrainian black soil (chornozem in Ukrainian) is a natural resource that, in theory, might have created conditions for the Indigenous people’s prosperity but led to the opposite consequences, instead of the wealth of locals — colonization and exploitation by stronger neighbors.

This exploitation carries with it depleted lands and cut centuries-old oaks. Resource extraction leads to the exhaustion of the environment and its irreversible changes.

A colonization is not interested in the future of that particular territory; the resources go to the metropolis.

To use the resource now, it is necessary to clear the land from its past: people’s memories and trees that can live a long time and be silent witnesses of the local history and sacred life. Trees carry the memory of forests; steppes are not just the absence of something. Steppes carry the memory of past generations in their bellies, externally covered with tempting pastures and fresh arable land.

This leads to constant erasure of material and immaterial heritage. So, every third Ukrainian generation faces the necessity of archaeology: to dig the knowledge of the generations before them. Every second generation finds itself in the timelessness of survival. This third generation, which should become a formed product of the life of close ancestors, must reconstruct the reality of the past generations through archaeological practices. The natural transfer of the heritage is broken. Grandchildren barely know the complete stories of their grandparents because many things are silenced, memories are repressed or are false. There is almost no chance that significant material heritage is transferred through generations. Artifacts of the common culture are destroyed, damaged, hidden, stolen, lost; especially in cities like Kharkiv.

New generations have to collect fragments of texts, search for stucco under layers of wallpaper, exhume mass graves and abandoned graves, and collect bricks to imagine what they were part of. They try to find connections that are lost in the material but not lost in the collective memory.

Yes, this memory resembles a landfill, but the attentive gaze of a researcher, who examines the material with an archaeologist’s optics, can recreate an entire ecosystem from several dinosaur bones. There is a legend that when the iconic constructivist masterpiece Derzhprom was built in Kharkiv in the 1920s, they found a mammoth bone.

1 It refers to the Executed Renaissance or “Red Renaissance” (Ukrainian: Rozstriliane vidrodzhennia, Chervonyi renesans), the generation of Ukrainian language poets, writers, and artists of the 1920s and early 1930s that was formed mostly in Kharkiv and Kyiv. As a result of the Ukrainian War of Independence’ defeat to the Bolsheviks, the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (UkSSR) arose with its capital in Kharkiv, encouraging a wide cultural autonomy for Ukrainians, before Joseph Stalin reversed those policies in favor of State centralization, Socialist Realism, and Russification. The absolute majority of the Executed Renaissance representatives were killed or purged by the Kremlin in the 1930s.

Thus, they discovered the past through the future and forever sealed this situation.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that one of the leaders of the generation (although there are, in fact, no leaders), Mahran Tata, is an archaeologist. Only in this way is it possible to imagine where and how dinosaurs, mammoths, and previous generations of Ukrainians lived and dreamed.

They live in Kharkiv, the city with a rich (but hidden under the dust of the 20th century) avant-garde tradition that grew up on the barren provincial land of Kharkiv. It has a significant flaw: it is only 30 kilometers from the border with the Russian Federation. Russians create new stumps from Ukrainian lives. Hundreds of thousands are being killed. Irreplaceable losses.

This is a generation of attentive, sensual and sensitive, tender and disturbing people.

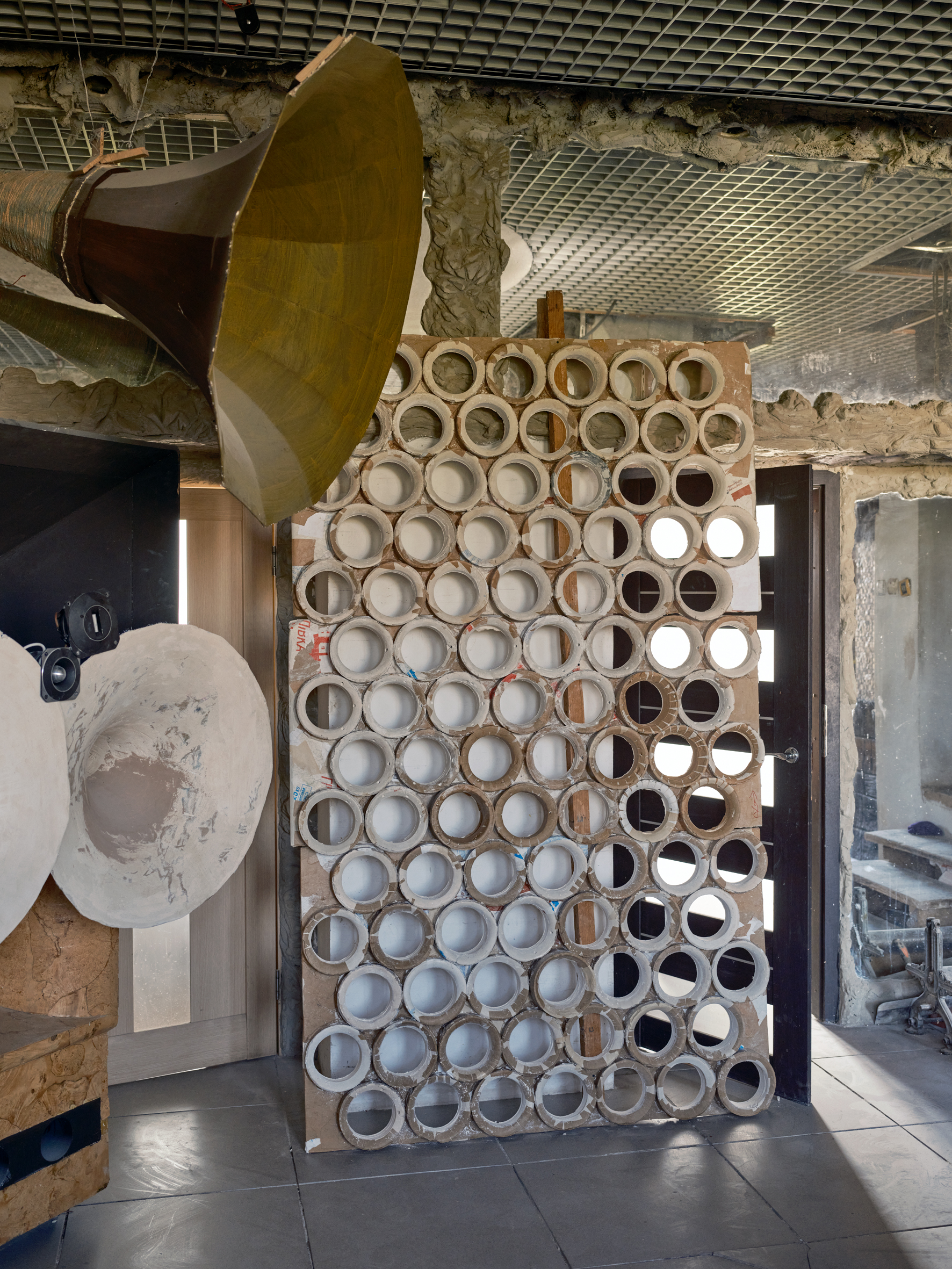

A generation that is growing. This is a generation of real people that has the inner power to grow. Like the one seeds have. And create. They create their own spaces; they create their own events; they create their own art. They create something to make sure the third generation will not have to dig up and collect debris but will stand firmly on this earth.

These people do not have the luxury of developed cultural infrastructure, venues, media, critics, or even the audience. They have neither support from the state nor institutional support, nor institutions as such, nor money.

They are a generation deprived of internal and external security due to a full-scale war — deprived of health, prospects, and social approval. Their city, homes, spaces, and lives can be damaged or destroyed at any moment. They have no ambition to fit into the current conjuncture, but there is no opposition to it either. They are not followers of any artistic trend except the trend of life itself. They are people in their twenties in the dramatic 2020s. Whose lives have too many similarities with the 1920s in Kharkiv, which was a tragedy. And then became a legend.

As 100 years ago, in the 1920s, theater, cinema, poetry, and art sprouts were intertwined in a chaotic garden of fruit and berry thickets. These do not so much feed the hungry as give life to new ones, especially when these fruits and berries fall to the ground, even though the previous garden was squelched by Russians 100 years ago. 1

This generation’s only desire is to do things without which it is impossible to live. They grow like sprouts from stumps simply because such is the logic of life. Life necessarily reproduces itself. It regenerates.

Today, for the first time in history, we have the Main Land, The State of Ukraine. Everything significant appears there. The source of strength in human society is called “culture.” This source nourishes everyone who is connected to it. They create it. And it intertwines.

Thursday October 30, 2025 in The Hague: Paleiskerk

UNBROKEN: VOICES FROM UKRAINE by Classical NOW!

Lux Aeterna Revoice - Symbolic echoes

“The Ukrainian vocal ensemble Alter Ratio (“different thinking”) is causing an international sensation. The twelve singers make their Dutch debut with Lux Aeterna Revoice. György Ligeti’s iconic Lux Aeterna is performed alongside four brand-new works dedicated to Ukrainian artists who lost their lives in the war.

This impressive and innovative programme sees each composer intertwine the singers’ voices with electronic soundscapes in a unique and personal way. Ligeti’s sixteen-part masterpiece acquires a new, poignant resonance. The twelve singers of Alter Ratio are joined by four electronic layers — echoes of voices silenced by war, in collaboration with the striking photographic exhibition Regeneration Generation by Christian van der Kooy.

UNBROKEN: VOICES FROM UKRAINE by Classical NOW!

Lux Aeterna Revoice - Symbolic echoes

“The Ukrainian vocal ensemble Alter Ratio (“different thinking”) is causing an international sensation. The twelve singers make their Dutch debut with Lux Aeterna Revoice. György Ligeti’s iconic Lux Aeterna is performed alongside four brand-new works dedicated to Ukrainian artists who lost their lives in the war.

This impressive and innovative programme sees each composer intertwine the singers’ voices with electronic soundscapes in a unique and personal way. Ligeti’s sixteen-part masterpiece acquires a new, poignant resonance. The twelve singers of Alter Ratio are joined by four electronic layers — echoes of voices silenced by war, in collaboration with the striking photographic exhibition Regeneration Generation by Christian van der Kooy.

Each of the newly composed works explores the theme of memory and loss in its own way. In Disappearing Voices, Maxim Kolomiiets gives voice to the fragility of sounds fading into darkness. In Sub Rosa, Maxim Shalygin creates a labyrinth of sound where melodies and electronics alternately embrace and contradict one another. Alla Zagaykevych evokes a constant motion between hope and despair in Psalms of Falling, while in Phosphorus, Peter Kerkelov lets the light of vanished souls glow as beacons for the living.”

![]()