Book reviews

CPhMag - Conscientious Photography Magazine

Anastasiia by Jörg Colberg

The world of documentary photography adheres to rules that borrow heavily from traditional journalism. With few exceptions, the (typically outside) observer enters a space or approaches a topic with the idea of providing as objective as possible a picture. Obviously, true objectivity cannot be had — humans aren’t robots. The smart documentarian will acknowledge as much and proceed with this inherent contradiction of her or his endeavour in mind. Conclusions and/or judgments might be offered, but even they tend to usually end up being on the cautious side.

There is much to be said for that model, as we are all learning these days as alternative hyper-partisan outlets undermine everything traditional journalism has come to stand for, to disseminate what can only be described as blatant propaganda.

At the core of all this stands the idea of truth. Absolute truth is unattainable — this might be the only thing even the most extreme poles of human endeavour, religion and science, can agree on. In a nutshell, aiming for as much objectivity as possible is an attempt to get as close to a incontestable truth as possible, without ever being able to fully reach it. Ignoring those hyper-partisan outlets (which act in bad faith as far as the greater good is concerned), objectivity is not necessarily the only way to reach a — note: not the — truth. After all, there are many kinds of truths: human life is too complex to make do with just one.

I’m personally very interested in expanded explorations of the documentary form because I believe that insight into the human condition needs to acknowledge the many grey zones. This is not to say that I deny the value and/or validity of traditional documentary work — quite on the contrary. But I’m intrigued by having what I believe in challenged not just through facts but also through an exposure to the unexpected.

Christian van der Kooy‘s Anastasiia is a prime example of a recent book that pushes the boundaries of the documentary form. It does so by explicitly incorporating aspects that I suspect many documentarians would shy away from. On a trip to Ukraine, the location explored in the book, the photographer met a young woman who for reasons that aren’t entirely clear picked him up at some metro station. They fell in love. The developing relationship immediately becomes part of the overall narration — a long-distance relationship, sustained through the exchange of messages and through Skyping.

While the relationship plays a large part, the book does not center on it. Instead, its focus is the country, Ukraine, and its recent (and ongoing) turmoil, caused by the overthrow of a corrupt regime and the subsequent Russian invasions in Crimea and eastern provinces. Throughout the book, both the photographer and his girlfriend attempt to come to grips both with the country itself and their relationship, both providing their own voices through text (curiously, Van der Kooy’s messages to Anastasiia are absent). For the photographer, it’s an attempt to come to grips with another country that, while being part of Europe, feels alien. For the young woman, the challenges are not that dissimilar as what used to be taken for granted is now being challenged, and old ideas and norms are being replaced by new ones.

The mix of the intensely personal with what one would consider documentary material in addition to the mix of two clearly distinct voices (that also try to make sense of each other) lends the book a dimension absent from many (actually most) other documentary photobooks I know. There is a clear red thread running through the book, but it’s one of human uncertainty and of longing. It’s a book about life under specific circumstances, two people living their lives while being close to each other — mentally close when not being physically close. Can a country be understood by any one person at any moment in time? It’s doubtful. There can always be a picture painted (or written — should historians read this review), but inevitably, the picture will change.

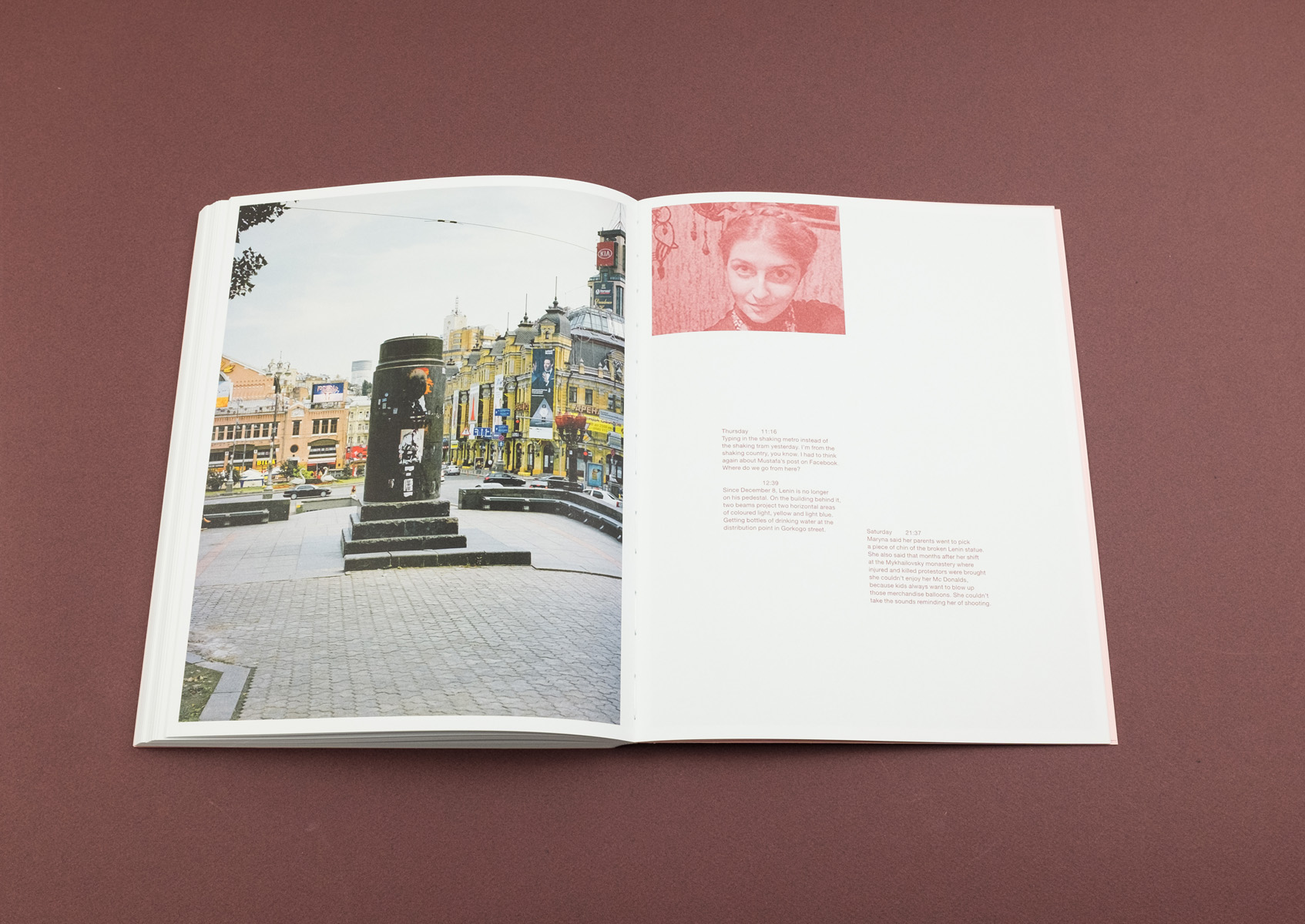

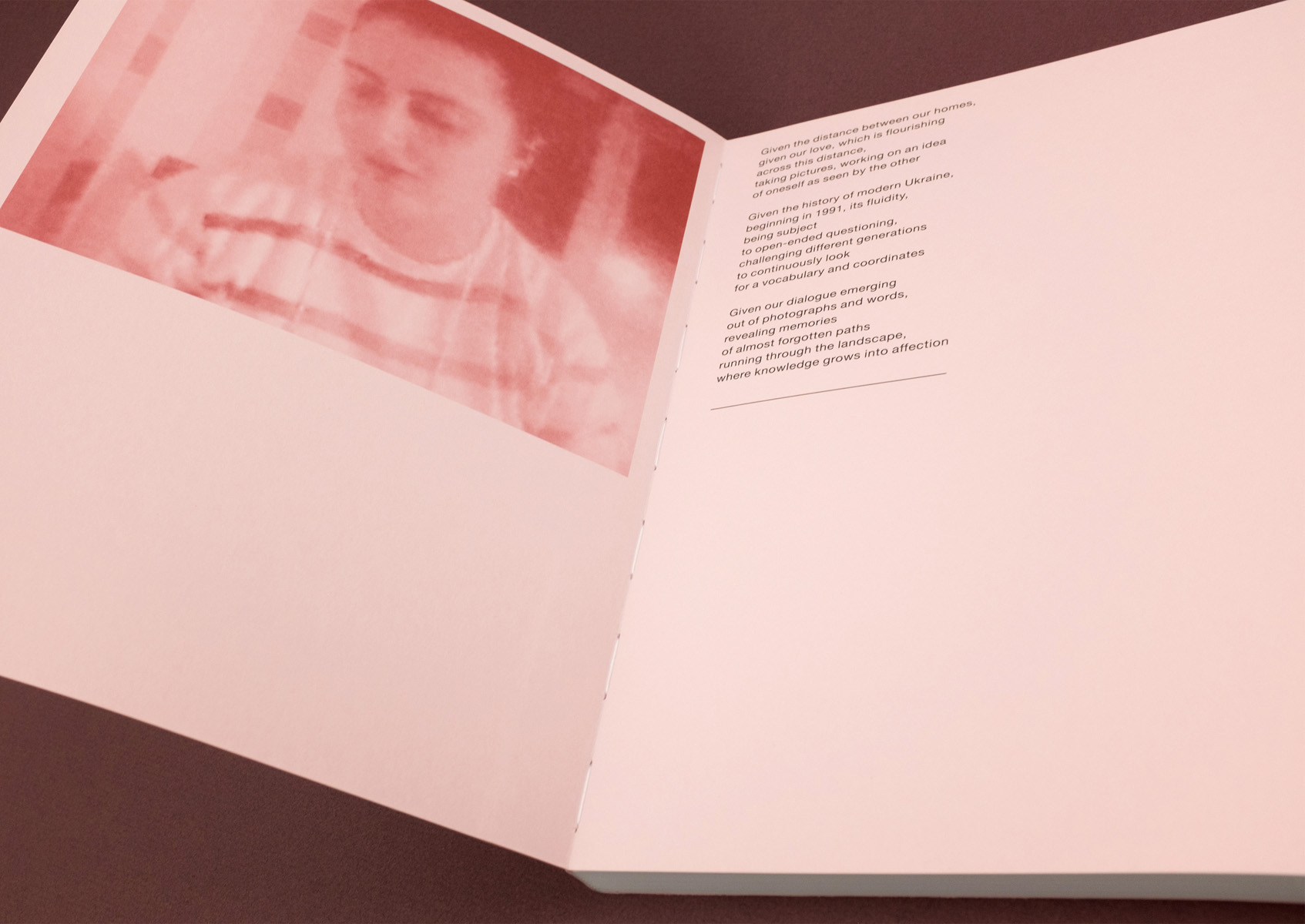

The material in the book is presented and organized through some very basic and simple design choices, making the viewer’s/reader’s job very simple. Skype screen-grab images are monochromatic — the pinkish hue that can be seen on the cover. Anastasiia’s writing and text are presented in the same colour. In contrast, Van der Kooy’s photographs are shown in full colour, and his writing is black.

I was unable to read Anastasiia in one sitting, something that would have been easily possible, simply because I didn’t want the experience of spending time with the book to end. I can only say that for very, very few photobooks that arrive at my doorstep. As much as I am tired of the seemingly endless barrage of very personal work in photoland — to give just one example: how many more family-photography projects do we need?), here I felt I was in the presence of something not only unexpected but also deeply engaging, deeply affecting.

It’s very likely that my placing of the book into the larger context of documentary photography will have a lot of people disagree. In my photobook taxonomy, I placed it under subjective documentary. But I do think there’s a time and place for an expansion of the idea of what the documentary form is and can be, in part because of the propaganda counter push by the hyper-partisan outlets: one of the most problematic aspects of the documentary form is its insistence on as objective a truth as possible. Hyper-partisan outlets have been deftly using this Achilles heel by pointing out minor inconsistencies in other people’s reporting while themselves pushing blatantly false if not outright nonsensical material. Whether or not the fight against those acting in bad faith can be won remains to be seen.

One way to disarm the partisans and professional liars might be to opt out of playing this one-sided game and to, instead, embrace forms such as the one used in Anastasiia. This not only expands ideas of the documentary to include other voices, here that of a person living in the area in question, but it also acknowledges the inherent shortcomings of the documentary form while not giving up on the quest for a larger truth anyway.

Highly recommended.

![]()

The material in the book is presented and organized through some very basic and simple design choices, making the viewer’s/reader’s job very simple. Skype screen-grab images are monochromatic — the pinkish hue that can be seen on the cover. Anastasiia’s writing and text are presented in the same colour. In contrast, Van der Kooy’s photographs are shown in full colour, and his writing is black.

I was unable to read Anastasiia in one sitting, something that would have been easily possible, simply because I didn’t want the experience of spending time with the book to end. I can only say that for very, very few photobooks that arrive at my doorstep. As much as I am tired of the seemingly endless barrage of very personal work in photoland — to give just one example: how many more family-photography projects do we need?), here I felt I was in the presence of something not only unexpected but also deeply engaging, deeply affecting.

It’s very likely that my placing of the book into the larger context of documentary photography will have a lot of people disagree. In my photobook taxonomy, I placed it under subjective documentary. But I do think there’s a time and place for an expansion of the idea of what the documentary form is and can be, in part because of the propaganda counter push by the hyper-partisan outlets: one of the most problematic aspects of the documentary form is its insistence on as objective a truth as possible. Hyper-partisan outlets have been deftly using this Achilles heel by pointing out minor inconsistencies in other people’s reporting while themselves pushing blatantly false if not outright nonsensical material. Whether or not the fight against those acting in bad faith can be won remains to be seen.

One way to disarm the partisans and professional liars might be to opt out of playing this one-sided game and to, instead, embrace forms such as the one used in Anastasiia. This not only expands ideas of the documentary to include other voices, here that of a person living in the area in question, but it also acknowledges the inherent shortcomings of the documentary form while not giving up on the quest for a larger truth anyway.

Highly recommended.

Urbanautica Institute

In dialogue with Steve Bisson

«We hear it everywhere these days. It's time for a big sweep of narrative that becomes the myth of our times. A story which helps us fight through the discomforting changes that are upon us. A new story and everything's solved. Maybe but probably not. Judged by the current streams of storytelling, despite of the varieties and overwhelming presence of stories, the stories are coming up short.»

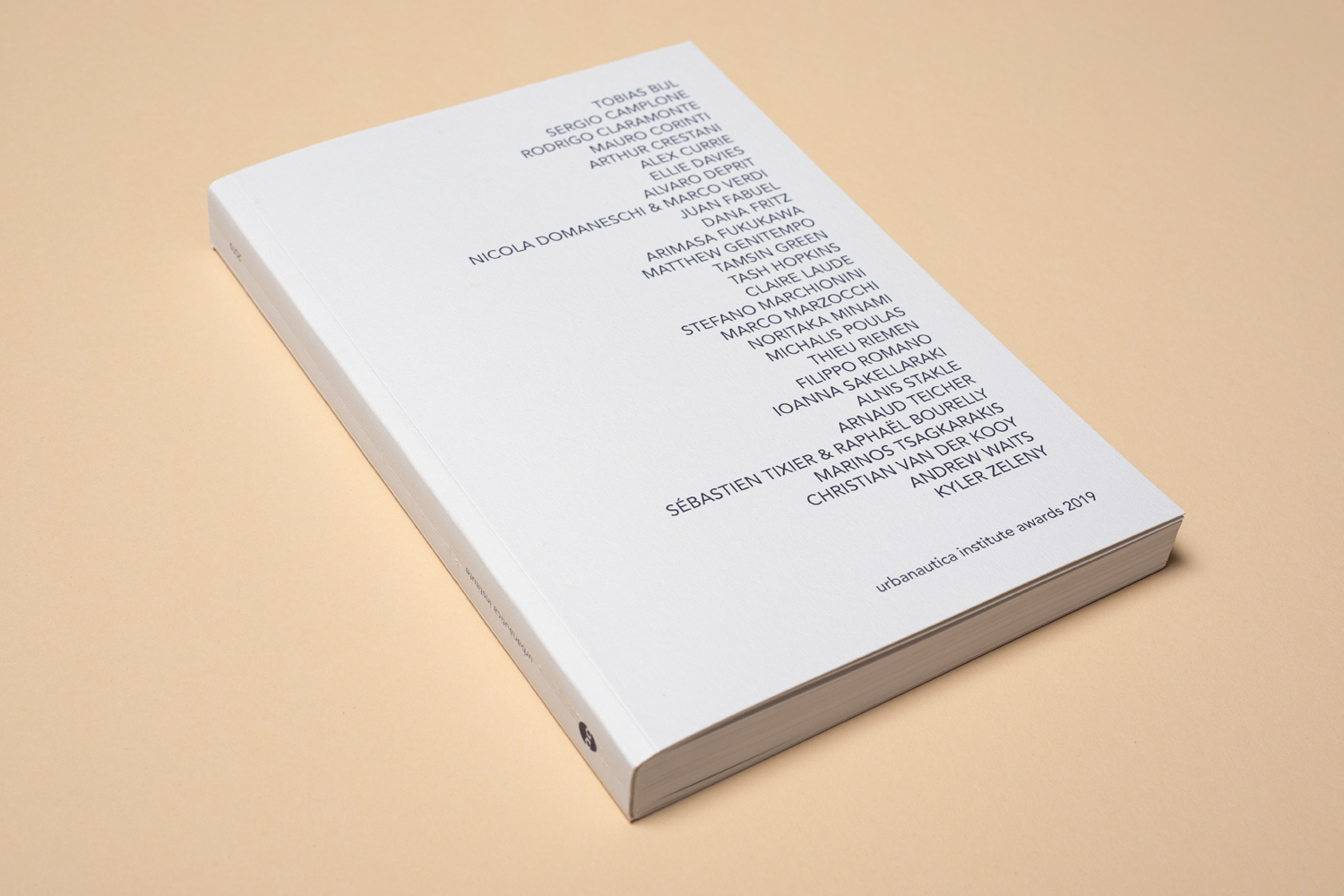

Christian Van der Kooy is one the finalist of Urbanautica Institute Awards 2019. His series 'Anastasiia' was featured in the catalog of our annual awards.

Chris could you please tell us about where you grew up. What kind of place was it? And then photography. How it all started? What are your memories of your first shots?

Christian Van Der Kooy (CV): Until I became nine years old we moved every three years to a different part of the Netherlands, before settling down in the forest-rich central part around Arnhem. My mother was a primary school teacher and my father a steward on the Middachten estate, a Dutch heritage site. His company managed and supervised the castle, forest, park and gardens for the 25th Lord of Middachten; exercising stewardship on lease, taxes, forestry and gamekeeping. Growing up close-by these premises took me on a journey, from orangery to haystack, cellar to attic, and showed me how the perceptions of houses and places shape our thoughts, memories and dreams. In retrospect, it showed me how I look at landscape, at nature and culture.

A precious memory is making some pictures in the parked DAF600 car of my grandfather. Him photographing me while I firmly hold the steering wheel standing on the driver's seat, and me photographing him smiling for the camera. I must have been four or five. After he passed away I inherited his black top hat from the wedding which I didn't know still existed, but instantly recognized from a framed black-and-white photograph on my mother's desk. When trying to fit it on I realized his head was much smaller than mine. The top hat gave me the focus to relate again to the surroundings of my grandparents' home and garden, with the red squirrels and cooing pigeons. What I fundamentally learned from my grandfather is the pure love of just wandering around in solitude, trying to pin down the spirit of place.

What about your educational background? How do you relate to this? Any takeaways? Any meaningful courses? Any professor or teacher you remember well?

CV: I graduated in 2006 from the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. During my study, I had the privilege to work with and assist my documentary photography teachers Raimond Wouda and Guus Rijven. They both encouraged me to change my gaze, do substantial literature research and formulate my questions before taking out a camera. They conveyed the sensual riches of a 4x5" negative, and described the camera as an omniscient observer making people and environment merge. I became excited about experimenting with the height of the camera-eye, beyond normal human perspective, because it allowed for renderings of a deeper and more lyrical exploration of landscape. It still thrills me that they made sure I will never again see ordinary places in ordinary ways.

What do you think about photography in the era of digital and social networking? How is the language evolving and impacting daily life of people and communities in your opinion?

CV: Humans have always lived by stories; everything we know is a story. About our relationship to the environment, about our relationship to each other. And, as any historian could confirm, every culture, every civilisation has been built on some kind of narrative structure. Our present (digital) world is no different. It is shaped by stories, whether or not it has an evanescent touch of whimsy that is lost in translation. It's a habit for humans to use story to become part of something, to belong somewhere. Our brains are still ‘wired’ for stories. We need stories to ground ourselves. We need them to engage with the globalized network societies we live in.Narrative still has a great power in this world. It can inspire us, urge us for action, enables us to imagine new possibilities, for social organisation and for personal development: it is the potential of fiction to intervene in our understanding of our social world and our perception of opportunity for action within it.

I am confident that fiction, subjective documentary, has relevance – even utility – in addressing the overwhelming acceleration of change that is upon us. Fiction, ideally, should provoke us to question and challenge the everyday world we have been given. Poetry, installation-art, film and photography have a critical role to play in generating and embracing the process of change by which the future invades our lives. As it is impossible to see all details of a panorama within your field of vision, you're unable to fully see how it influences our experience of present society. In my work I hope to reveal a way of seeing and how I have learned to understand and ultimately feel what for me gives a story its identity and character.

Fast interconnections and instant sharing. How this is affecting the role of a documentary photographer and your own practice?

CV: «Perhaps instead of standing by the river bank scooping out water, it’s better to immerse yourself in the current, and watch how the river comes up, flows smoothly around your presence, and gently reforms the other side like you were never there.» (Paul Graham, A Shimmer of Possibility)

Technology plays an essential role in what I do and it transforms the way in which I interact with the world. My process of finding subjects and doing research is very much tied to the Internet. It gives me a place to get information and provides me with a matrix that somehow captured the invisible weave of culture. It gives me a destination, even before leaving the studio for the road.Establishing interconnections in combination with for example the Instagram platform has the ability to combine formalism and detail together with action and the unexpected. It's what I enjoy to research more and integrate in my photography language. Consequently, because of platform structures nowadays, other voices will come through all the time, marking their territory with images and stories. I hope that this stream of stories will encourage something of value to stand out, as it has done for me, by taking the time to look and relook.

About your work now. How would you introduce yourself as an author or described your personal methodology? Your visual exploration...

CV: We hear it everywhere these days. It's time for a big sweep of narrative that becomes the myth of our times. A story which helps us fight through the discomforting changes that are upon us. A new story and everything's solved. Maybe but probably not. Judged by the current streams of storytelling, despite of the varieties and overwhelming presence of stories, the stories are coming up short.I start my artistic research by recognizing this puzzling situation regarding story: there is no shortage of storied information, of narrative material. One could even argue that we are blinded by the offering. So, perhaps, it is in the way stories are being told. Maybe the stories we need are already here, we just have to regard them differently? Maybe they have to be rediscovered and channelled differently?My aim is to model a form of critical and creative discourse through visual and textual exploration of narrative constructs. The interplay of words and images give a story a kiss of life. The keynote of this process is to analyse and interpret reality by creating a new context. Sense of place lies at the heart of my artistic practice. It makes me smile if my work has provided the occasion for new, ingenious, and focused reflections to viewers and readers.

Can you introduce the work 'Anastasiia' that was shortlisted or Urbanautica Institute Awards. What are the basic motivations and assumptions of this project?

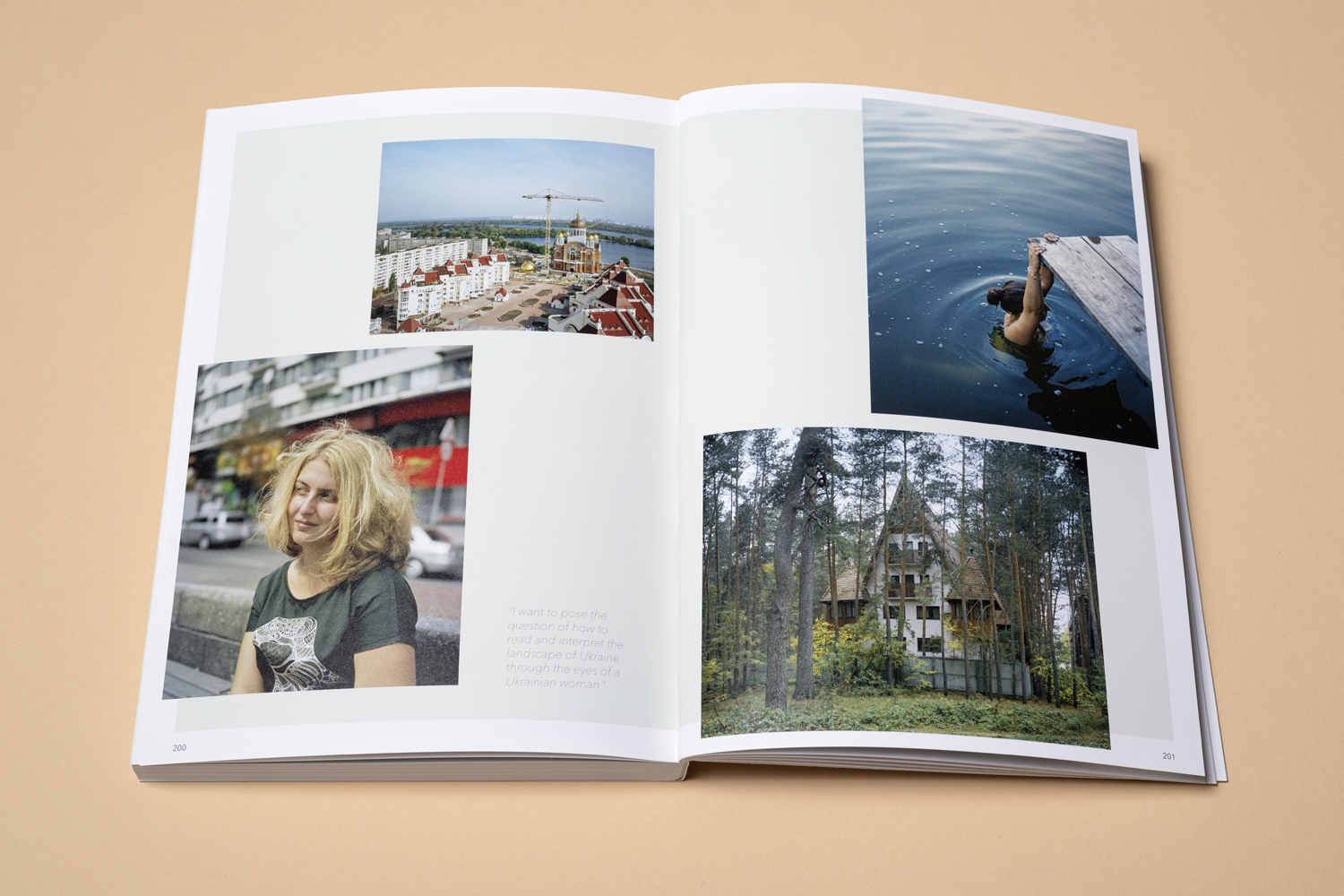

CV: My proposition is to reinforce narrative as vehicle that helps us anticipate change. Anticipate transformations. Whether they are social, economic, scientific or religious, we are dealing with the absence of an applicable attitude towards story, not with an indispensable loss of it. In the wake of this proposition, my intention is to revive the re-imagining of the world through storytelling.However subjective the outlook, I believe that the only subjects that embody change are moving in long, very long time spans – relationships, landscapes and the history of society. In the time when people demand new narrative I want to pose the question of how to read and interpret the landscape of Ukraine through the eyes of a Ukrainian woman. I consider the complexity of the reciprocal manner in which a person engages with a landscape from a variety of personal (emotional) and social perspectives, and wonder if we'll ever be able to recognise and overcome our bias.

Christian Van der Kooy is one the finalist of Urbanautica Institute Awards 2019. His series 'Anastasiia' was featured in the catalog of our annual awards.

Chris could you please tell us about where you grew up. What kind of place was it? And then photography. How it all started? What are your memories of your first shots?

Christian Van Der Kooy (CV): Until I became nine years old we moved every three years to a different part of the Netherlands, before settling down in the forest-rich central part around Arnhem. My mother was a primary school teacher and my father a steward on the Middachten estate, a Dutch heritage site. His company managed and supervised the castle, forest, park and gardens for the 25th Lord of Middachten; exercising stewardship on lease, taxes, forestry and gamekeeping. Growing up close-by these premises took me on a journey, from orangery to haystack, cellar to attic, and showed me how the perceptions of houses and places shape our thoughts, memories and dreams. In retrospect, it showed me how I look at landscape, at nature and culture.

A precious memory is making some pictures in the parked DAF600 car of my grandfather. Him photographing me while I firmly hold the steering wheel standing on the driver's seat, and me photographing him smiling for the camera. I must have been four or five. After he passed away I inherited his black top hat from the wedding which I didn't know still existed, but instantly recognized from a framed black-and-white photograph on my mother's desk. When trying to fit it on I realized his head was much smaller than mine. The top hat gave me the focus to relate again to the surroundings of my grandparents' home and garden, with the red squirrels and cooing pigeons. What I fundamentally learned from my grandfather is the pure love of just wandering around in solitude, trying to pin down the spirit of place.

What about your educational background? How do you relate to this? Any takeaways? Any meaningful courses? Any professor or teacher you remember well?

CV: I graduated in 2006 from the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. During my study, I had the privilege to work with and assist my documentary photography teachers Raimond Wouda and Guus Rijven. They both encouraged me to change my gaze, do substantial literature research and formulate my questions before taking out a camera. They conveyed the sensual riches of a 4x5" negative, and described the camera as an omniscient observer making people and environment merge. I became excited about experimenting with the height of the camera-eye, beyond normal human perspective, because it allowed for renderings of a deeper and more lyrical exploration of landscape. It still thrills me that they made sure I will never again see ordinary places in ordinary ways.

What do you think about photography in the era of digital and social networking? How is the language evolving and impacting daily life of people and communities in your opinion?

CV: Humans have always lived by stories; everything we know is a story. About our relationship to the environment, about our relationship to each other. And, as any historian could confirm, every culture, every civilisation has been built on some kind of narrative structure. Our present (digital) world is no different. It is shaped by stories, whether or not it has an evanescent touch of whimsy that is lost in translation. It's a habit for humans to use story to become part of something, to belong somewhere. Our brains are still ‘wired’ for stories. We need stories to ground ourselves. We need them to engage with the globalized network societies we live in.Narrative still has a great power in this world. It can inspire us, urge us for action, enables us to imagine new possibilities, for social organisation and for personal development: it is the potential of fiction to intervene in our understanding of our social world and our perception of opportunity for action within it.

I am confident that fiction, subjective documentary, has relevance – even utility – in addressing the overwhelming acceleration of change that is upon us. Fiction, ideally, should provoke us to question and challenge the everyday world we have been given. Poetry, installation-art, film and photography have a critical role to play in generating and embracing the process of change by which the future invades our lives. As it is impossible to see all details of a panorama within your field of vision, you're unable to fully see how it influences our experience of present society. In my work I hope to reveal a way of seeing and how I have learned to understand and ultimately feel what for me gives a story its identity and character.

Fast interconnections and instant sharing. How this is affecting the role of a documentary photographer and your own practice?

CV: «Perhaps instead of standing by the river bank scooping out water, it’s better to immerse yourself in the current, and watch how the river comes up, flows smoothly around your presence, and gently reforms the other side like you were never there.» (Paul Graham, A Shimmer of Possibility)

Technology plays an essential role in what I do and it transforms the way in which I interact with the world. My process of finding subjects and doing research is very much tied to the Internet. It gives me a place to get information and provides me with a matrix that somehow captured the invisible weave of culture. It gives me a destination, even before leaving the studio for the road.Establishing interconnections in combination with for example the Instagram platform has the ability to combine formalism and detail together with action and the unexpected. It's what I enjoy to research more and integrate in my photography language. Consequently, because of platform structures nowadays, other voices will come through all the time, marking their territory with images and stories. I hope that this stream of stories will encourage something of value to stand out, as it has done for me, by taking the time to look and relook.

About your work now. How would you introduce yourself as an author or described your personal methodology? Your visual exploration...

CV: We hear it everywhere these days. It's time for a big sweep of narrative that becomes the myth of our times. A story which helps us fight through the discomforting changes that are upon us. A new story and everything's solved. Maybe but probably not. Judged by the current streams of storytelling, despite of the varieties and overwhelming presence of stories, the stories are coming up short.I start my artistic research by recognizing this puzzling situation regarding story: there is no shortage of storied information, of narrative material. One could even argue that we are blinded by the offering. So, perhaps, it is in the way stories are being told. Maybe the stories we need are already here, we just have to regard them differently? Maybe they have to be rediscovered and channelled differently?My aim is to model a form of critical and creative discourse through visual and textual exploration of narrative constructs. The interplay of words and images give a story a kiss of life. The keynote of this process is to analyse and interpret reality by creating a new context. Sense of place lies at the heart of my artistic practice. It makes me smile if my work has provided the occasion for new, ingenious, and focused reflections to viewers and readers.

Can you introduce the work 'Anastasiia' that was shortlisted or Urbanautica Institute Awards. What are the basic motivations and assumptions of this project?

CV: My proposition is to reinforce narrative as vehicle that helps us anticipate change. Anticipate transformations. Whether they are social, economic, scientific or religious, we are dealing with the absence of an applicable attitude towards story, not with an indispensable loss of it. In the wake of this proposition, my intention is to revive the re-imagining of the world through storytelling.However subjective the outlook, I believe that the only subjects that embody change are moving in long, very long time spans – relationships, landscapes and the history of society. In the time when people demand new narrative I want to pose the question of how to read and interpret the landscape of Ukraine through the eyes of a Ukrainian woman. I consider the complexity of the reciprocal manner in which a person engages with a landscape from a variety of personal (emotional) and social perspectives, and wonder if we'll ever be able to recognise and overcome our bias.

The intention of the story is to share the personal empowerment of Anastasiia through a narrative-driven dialogue with her lover, the photographer. Their conversation is not about the outcome but an end in itself. By articulating in greater depth the ways of seeing and being in the landscape, she tells a story of encounter and experience, a mode of inhabiting the world.

Anastasiia is above all an insight into Ukrainian everyday life through the lovers’ intimacy. Emotion and sense of place form an ontological basis for the human capacity to experience meaning. This is part of our ordinary bodily experience, the means by which we touch the world and are in turn touched by it. The dialogue in Anastasiia represents a universal story: that individuals interpret their surroundings differently and that it remains uncharted territory to analyse their own experiences and perception. The establishment of your personal identity, your self, raises existential questions on the relationship with the other. How well do I know the person with whom I have a relationship? Does the relationship with the other become a part of my identity?

The project developed into a book. Tell us about this experience... And how in your sense the book digested your intentions?

CV: Can Ukraine be understood by anyone person at any moment in time? By me as a foreign photographer? By Anastasiia, born and raised in Kyiv? I don't think Anastasiia, She Folds Her Memories Like A Parachute is more than an attempt to come to grips. To be able to see it in other ways: twisted, sparked, flipped; and to understand and feel that Ukraine is changing, gradually gaining momentum.

The crucial moment the book came together was when I realized that it is not me who holds the key to this story, but the protagonist Anastasiia herself. Our continuous dialogue granted us time to be quiet, to pause and reflect, come back to previous (mis)conceptions and make associations between my pictures and places dear to Anastasiia. She recognizes the layers of history, the anomalies, the good spots and the dark corners of Ukraine. The image and the other, me and Anastasiia, are essentially synonymous. That is, what remains is only our desire or the fantasy that thrusts us toward each other.

My first draft had uncropped pictures on both the left and right pages and no text. The sequence of Anastasiia was wobbly and much darker, but I edited out a lot of the voyeuristic material because it forced the reader to go astray (Soviet nostalgia, nudes...). They would have overwhelmed the sequence. The rhythm of the dialogue was translated into a dynamic design by graphic designer and publisher Rob van Hoesel (The Eriskay Connection). Together we rewrote my previously written storylines, placed new markers and introduced a prologue and epilogue to the story. Half of the photography is making the pictures and half of it is editing the pictures. Editing things out is crucial. Rob has been crucial.

As flattered as I am, Jörg did grasp my intentions in a way I couldn’t write myself: «The mix of the intensely personal with what one would consider documentary material in addition to the mix of two clearly distinct voices (that also try to make sense of each other) lends the book a dimension absent from many (actually most) other documentary photobooks I know. There is aclear red thread running through the book, but it’s one of human uncertainty and of longing. It’s a book about life under specific circumstances, two people living their lives while being close to each other — mentally close when not being physically close.» Jörg M. Colberg.

I like your statement regarding this series «In Anastasiia I define the landscape admitting it will always be subjective, just like the memories, as it is constructed in the present.» Can you develop for us this concept and the relationship with memory?

CV: How to define the Ukrainian landscape? Imagine we were drawing cognitive or mental maps of the landscape. These memory maps were not a test of knowledge but were intended to provide information about a place, places that mattered enough to include them in our maps. We regard these maps as personal representations of Ukraine, as being another way of telling and reimagining our surroundings. During this extended process of looking, or being looked back at, Ukraine became very much part and parcel of our own biographies and identities and we developed a deep affection and visceral knowledge of it. Much of this experience sits in bodily memory and is impossible to convey and recount in mere words or pictures; photography by its very nature is elusive. The irony of any exploration of embodied identities in landscape, and the subjective experiences of ourselves is that, as a critical and creative discourse, it attempts to capture that what cannot be captured: much is lost or transformed in the process.

The photobook, in this particular case ‘Anastasiia, She Folds Her Memories Like A Parachute’, enables artistic interpretation, provides a constant framework, illuminates and creates awareness of the boundary between the picture and what is outside; the alternative world in the imagination.

You wrote that «In the current Ukrainian geopolitical discourse there is a quest to define and reflect on the cultural identity that embraces the mind-set of the generation born after independence (1991)». It's an interesting assumption. How do you feel your project impacted this debate and sociological debate? In other words how we can reduce the gap between artistic/documentary work and real society?

CV: That is very difficult to say, trivial really. In the first place, I'm an artist expressing my views through my works, not a pundit or key actor. It is not my role. The problem in this particular debate with "I’m entitled to my opinion" is that, all too often, it’s used to shelter beliefs that should have been abandoned, or are already abandoned by the people involved. I don't see a gap between my artistic practice and the real society as mentioned before. I do see a discrepancy in the society between the limited and contradictory changes (a feeling to be time-stretched; 'un-socialist realism') and the energetic hands-on mentality of the generation born after independence. This generation presents itself in a desire to know more and shares the unique spirit of the landscape that is part of who they are. Ukraine feels like a laboratory on the verge of a breakthrough.

Three books (not only of photography) that you recommend in relation to the project 'Anastasiia' or your photography or your interest in general.

CV: Dark Mountain Issue 14 - TERRA; Silence and Image - Essays on Japanese Photographers by Mariko Takeuch; Rain - A Natural and Cultural History by Cynthia Barnett.

Is there any show you’ve seen recently that you find inspiring?

CV: I've recently seen 'Walled Unwalled' on the big screen during IFFR. It still sends shivers up and down my spine. The video is a meticulously scripted series of performances recorded in an East Berlin, Cold War sound effects studios; beginning with the story of an American teenage boy growing weed in his private bedroom, to Oscar Pistorius shooting Reeva Steenkamp, and ending with the torture prison Saydnaya in Syria. Lawrence considers how solid structures (walls, doors or floors) are unable to prevent the flow of information or to remain a barrier between private and public space. In the last part about Saydnaya he focuses specifically on the way in which the prison walls were engineered so that the torture of one inmate would be broadcasted to fellow detainees by way of reverberation.

Earwitness Inventory (2018) - 'Walled Unwalled' (single channel 20 minute performance-video installation) by Lawrence Abu Hamdan. Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam.

What are you up to?

CV: I am still in the early stages of my research, but I can give a glimpse of my new project. By not setting foot on the Crimean peninsula I am researching the Ukrainian inherited landscape myths and memories of Crimeans. By conducting interviews, photographing and collecting pictures, I am trying to create a story of the past in the present. A story involving the representation of topography: the landscape, the sea, the sky, the sun; and integrate these features into a narrative of how it might have been. Into how it should have been?

Anastasiia is above all an insight into Ukrainian everyday life through the lovers’ intimacy. Emotion and sense of place form an ontological basis for the human capacity to experience meaning. This is part of our ordinary bodily experience, the means by which we touch the world and are in turn touched by it. The dialogue in Anastasiia represents a universal story: that individuals interpret their surroundings differently and that it remains uncharted territory to analyse their own experiences and perception. The establishment of your personal identity, your self, raises existential questions on the relationship with the other. How well do I know the person with whom I have a relationship? Does the relationship with the other become a part of my identity?

The project developed into a book. Tell us about this experience... And how in your sense the book digested your intentions?

CV: Can Ukraine be understood by anyone person at any moment in time? By me as a foreign photographer? By Anastasiia, born and raised in Kyiv? I don't think Anastasiia, She Folds Her Memories Like A Parachute is more than an attempt to come to grips. To be able to see it in other ways: twisted, sparked, flipped; and to understand and feel that Ukraine is changing, gradually gaining momentum.

The crucial moment the book came together was when I realized that it is not me who holds the key to this story, but the protagonist Anastasiia herself. Our continuous dialogue granted us time to be quiet, to pause and reflect, come back to previous (mis)conceptions and make associations between my pictures and places dear to Anastasiia. She recognizes the layers of history, the anomalies, the good spots and the dark corners of Ukraine. The image and the other, me and Anastasiia, are essentially synonymous. That is, what remains is only our desire or the fantasy that thrusts us toward each other.

My first draft had uncropped pictures on both the left and right pages and no text. The sequence of Anastasiia was wobbly and much darker, but I edited out a lot of the voyeuristic material because it forced the reader to go astray (Soviet nostalgia, nudes...). They would have overwhelmed the sequence. The rhythm of the dialogue was translated into a dynamic design by graphic designer and publisher Rob van Hoesel (The Eriskay Connection). Together we rewrote my previously written storylines, placed new markers and introduced a prologue and epilogue to the story. Half of the photography is making the pictures and half of it is editing the pictures. Editing things out is crucial. Rob has been crucial.

As flattered as I am, Jörg did grasp my intentions in a way I couldn’t write myself: «The mix of the intensely personal with what one would consider documentary material in addition to the mix of two clearly distinct voices (that also try to make sense of each other) lends the book a dimension absent from many (actually most) other documentary photobooks I know. There is aclear red thread running through the book, but it’s one of human uncertainty and of longing. It’s a book about life under specific circumstances, two people living their lives while being close to each other — mentally close when not being physically close.» Jörg M. Colberg.

I like your statement regarding this series «In Anastasiia I define the landscape admitting it will always be subjective, just like the memories, as it is constructed in the present.» Can you develop for us this concept and the relationship with memory?

CV: How to define the Ukrainian landscape? Imagine we were drawing cognitive or mental maps of the landscape. These memory maps were not a test of knowledge but were intended to provide information about a place, places that mattered enough to include them in our maps. We regard these maps as personal representations of Ukraine, as being another way of telling and reimagining our surroundings. During this extended process of looking, or being looked back at, Ukraine became very much part and parcel of our own biographies and identities and we developed a deep affection and visceral knowledge of it. Much of this experience sits in bodily memory and is impossible to convey and recount in mere words or pictures; photography by its very nature is elusive. The irony of any exploration of embodied identities in landscape, and the subjective experiences of ourselves is that, as a critical and creative discourse, it attempts to capture that what cannot be captured: much is lost or transformed in the process.

The photobook, in this particular case ‘Anastasiia, She Folds Her Memories Like A Parachute’, enables artistic interpretation, provides a constant framework, illuminates and creates awareness of the boundary between the picture and what is outside; the alternative world in the imagination.

You wrote that «In the current Ukrainian geopolitical discourse there is a quest to define and reflect on the cultural identity that embraces the mind-set of the generation born after independence (1991)». It's an interesting assumption. How do you feel your project impacted this debate and sociological debate? In other words how we can reduce the gap between artistic/documentary work and real society?

CV: That is very difficult to say, trivial really. In the first place, I'm an artist expressing my views through my works, not a pundit or key actor. It is not my role. The problem in this particular debate with "I’m entitled to my opinion" is that, all too often, it’s used to shelter beliefs that should have been abandoned, or are already abandoned by the people involved. I don't see a gap between my artistic practice and the real society as mentioned before. I do see a discrepancy in the society between the limited and contradictory changes (a feeling to be time-stretched; 'un-socialist realism') and the energetic hands-on mentality of the generation born after independence. This generation presents itself in a desire to know more and shares the unique spirit of the landscape that is part of who they are. Ukraine feels like a laboratory on the verge of a breakthrough.

Three books (not only of photography) that you recommend in relation to the project 'Anastasiia' or your photography or your interest in general.

CV: Dark Mountain Issue 14 - TERRA; Silence and Image - Essays on Japanese Photographers by Mariko Takeuch; Rain - A Natural and Cultural History by Cynthia Barnett.

Is there any show you’ve seen recently that you find inspiring?

CV: I've recently seen 'Walled Unwalled' on the big screen during IFFR. It still sends shivers up and down my spine. The video is a meticulously scripted series of performances recorded in an East Berlin, Cold War sound effects studios; beginning with the story of an American teenage boy growing weed in his private bedroom, to Oscar Pistorius shooting Reeva Steenkamp, and ending with the torture prison Saydnaya in Syria. Lawrence considers how solid structures (walls, doors or floors) are unable to prevent the flow of information or to remain a barrier between private and public space. In the last part about Saydnaya he focuses specifically on the way in which the prison walls were engineered so that the torture of one inmate would be broadcasted to fellow detainees by way of reverberation.

Earwitness Inventory (2018) - 'Walled Unwalled' (single channel 20 minute performance-video installation) by Lawrence Abu Hamdan. Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam.

What are you up to?

CV: I am still in the early stages of my research, but I can give a glimpse of my new project. By not setting foot on the Crimean peninsula I am researching the Ukrainian inherited landscape myths and memories of Crimeans. By conducting interviews, photographing and collecting pictures, I am trying to create a story of the past in the present. A story involving the representation of topography: the landscape, the sea, the sky, the sun; and integrate these features into a narrative of how it might have been. Into how it should have been?

Photographic Museum of Humanity

Who I was, Who I am, Who I will be? Who knows? by Colin Pantall

Christian van der Kooy's Anastasiia, she folds her memories like a parachute, is a poetic riff on the constancy of love set against the uncertainties of national identity. You choose your memories and your memories choose you, and you fold them like a parachute.

Anastasiia, She folds her memories like a parachute is a book of a love affair mixed with the history of Ukraine. It’s a book of memories then, a book about the past, and how the past is defined by the present. The clue to its construction is embedded in the title (a line from a poem by Joseph Brodsky). It’s a great title for a sophisticated book, one that contains within it the notion that the past is something that is with us all the time, that is not something in the past as we know it but is very much something we construct as time goes by.. We reinvent our past with every moment, with every word, with every image. We unfold it like a parachute, and let it take us down gently into the onward rush of the present. The past, if you like, is ahead of us.

Memory is a fabrication in this scheme of things, something we choose to create, something that makes the story worth telling, something that softens the blow. This book is an attempt by Anastasiia to define to her lover (the author) what it is to be Ukrainian, culturally, emotionally, and visually. The memories are told through images, while the words of Anastasiia recount her emotional ride through the romance, and the words of the narrator, Christian van der Kooy, tell the story of more distant people and place. It’s a book of a love affair that starts with the erotic jolt of a first glance outside a metro station, that then folds into the history of Ukraine, a history that since its latest reincarnation in 1991 has been contested by successive generations, by regional power struggles, and by outright war.

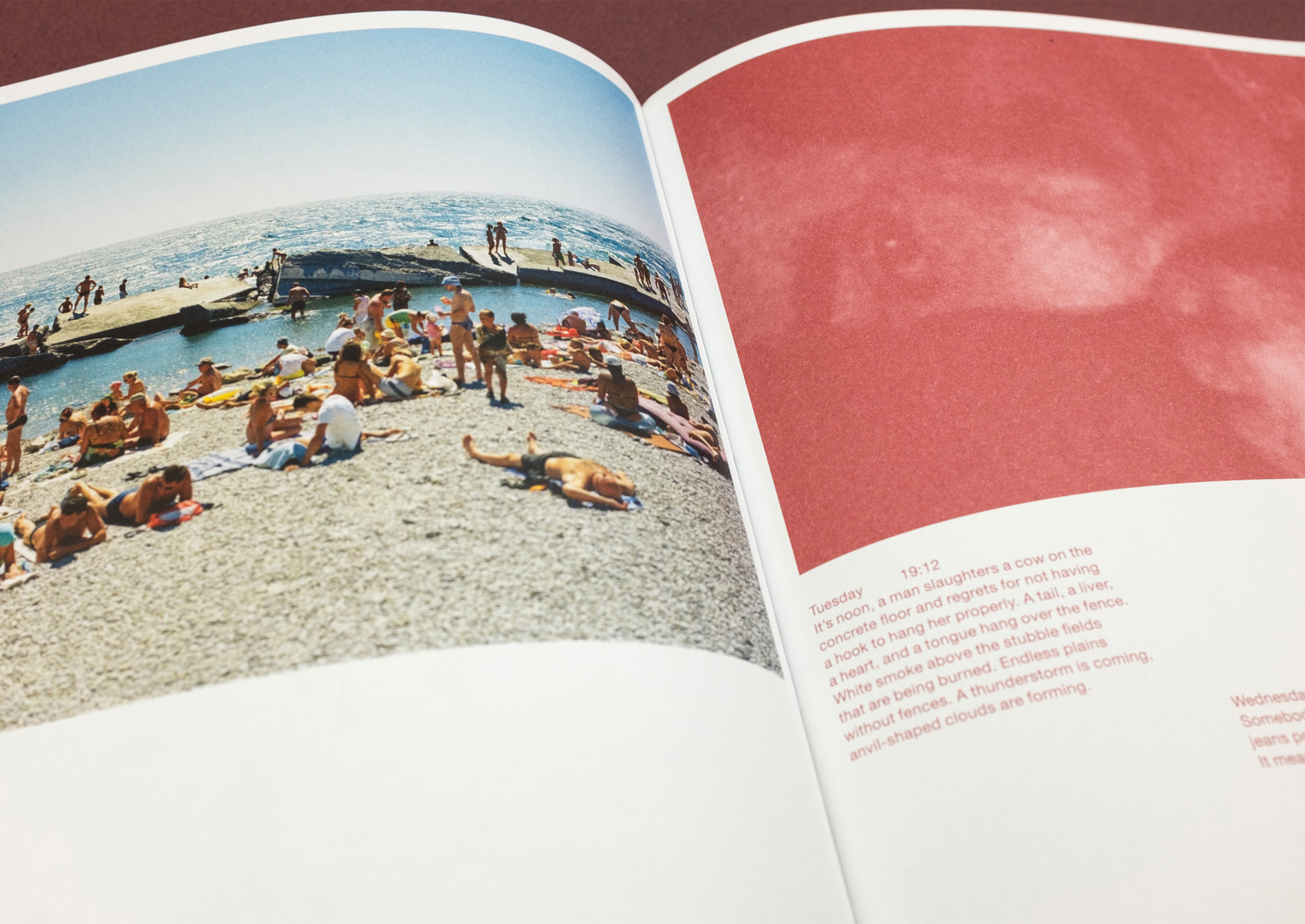

The main images start with an overview of Kyiv, of flats, red-tiled villas, and more modest homes rooved with corrugated iron testifying to the social as well as physical landscape. Then we move into a series of relaxed images of the city. There’s a portrait of Lucian, a thoughtful-looking man in a homemade helmet from the Maidan demonstrations of 2014, a paralysed dog with wheels where her back legs don’t work, a man sleeping in a field of beaten down weeds, the quiet inertia of parks in Odessa, a crowded beach in Crimea, and a man in hammer and sickle swimming trunks with a double crucifix round his neck.

Everything is still and slightly out of kilter, made to fit, made to look as though it is ordered and ‘belongs’, though beneath the surface nobody is quite sure what fits or what belongs. That’s as it should be, because nothing ever really fits. One image shows a group of people gathered around a small patch of grass. It looks like a party of some sort, but with nobody quite sure what is happening or what is going to happen.

What happens is the turmoil of 2014 and the resulting separatist conflict with Russia. In the light of this, the relative certainties of pre-war national identity are hinted at but largely unseen hyper-politicised nationalism. Kyiv is painted in the national colours of yellow and blue, histories, loyalties, meanings are redefined and all of a sudden the only thing left to cling to is the emotional bedrock of the relationship between Anastasiia and Christian. This is all that’s left because this is all that ever was, and that’s all that ultimately matters. It’s love that’s won, and this love is the memory that is folded like a parachute.

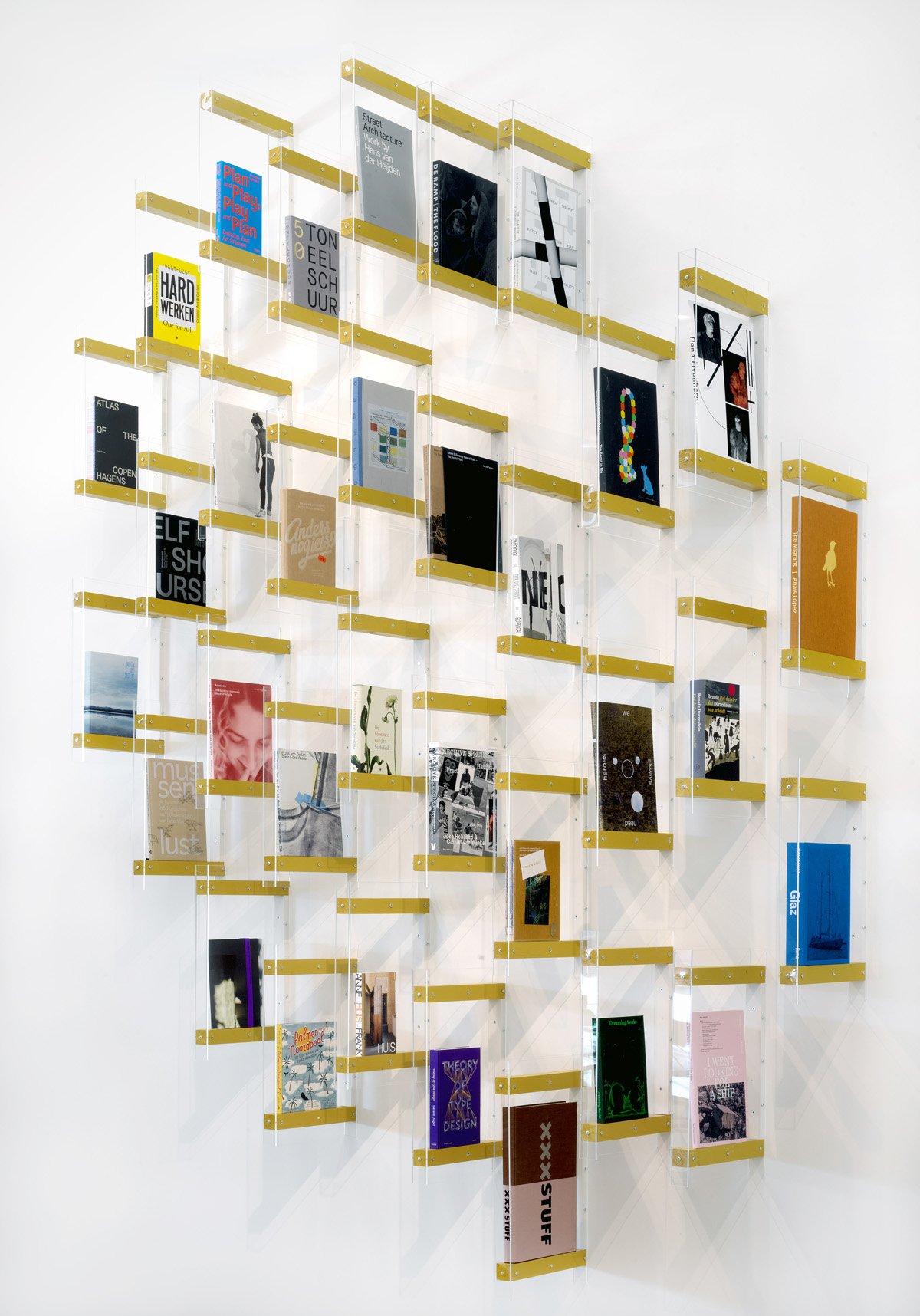

THE BEST DUTCH BOOK DESIGNS 2018

The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Each year, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and Stichting Best Verzorgde Boeken present an expert jury selection of the most outstanding book designs of the last twelve months. This year, a total of 33 books were picked from the 295 publisher-submitted titles released in 2018, and will go on display in the Stedelijk Museum’s Audi Gallery on 25 September.

The exhibited publications were chosen for their outstanding design, typography, image treatment, technical graphic production and the balance between form and content. Among those that made the final cut are tomes from well-known publishers, museum catalogues, corporate anniversary publications and rare finds from independent imprints.

The exhibited publications were chosen for their outstanding design, typography, image treatment, technical graphic production and the balance between form and content. Among those that made the final cut are tomes from well-known publishers, museum catalogues, corporate anniversary publications and rare finds from independent imprints.

This year’s finalists were selected by a panel of expert jurors consisting of Michaël Snitker (designer), Mijke Wondergem designer), Eelco van Welie (director of NAI010 publishers), Martijn Kicken (advisor at Drukkerij Tielen) and Suzanna Héman (assistant curator Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam).

The exhibition of The Best Dutch Book Designs has a long-standing tradition at the Stedelijk Museum. The inaugural presentation was mounted in 1932 and, with a few exceptions, has been held annually at the Stedelijk Museum ever since. The Dutch Best Verzorgde Boeken is the oldest contest of its kind in Europe to be judged by an expert jury.

Exhibition — 25 Sep until 30 Oct 2019

The exhibition of The Best Dutch Book Designs has a long-standing tradition at the Stedelijk Museum. The inaugural presentation was mounted in 1932 and, with a few exceptions, has been held annually at the Stedelijk Museum ever since. The Dutch Best Verzorgde Boeken is the oldest contest of its kind in Europe to be judged by an expert jury.

Exhibition — 25 Sep until 30 Oct 2019

Cultuur Cocktail

Zonder titel (vier volmaakte perziken op een schaal)

door Lise Lotte ten Voorde

Dit boek is een atlas. Een atlas van een mentale ruimte gevuld met betekenissen uit twee belevingswerelden.

![]()

Deze atlas stelt je in staat een reis te maken van buiten naar binnen, van West naar Oost en weer terug, een reis van het ene perspectief naar het andere, en van zachtheid via verwarring en irritatie naar begrijpend voelen. Het is een lange tocht, heen en weer, zonder duidelijke bestemming en met verlangen als tijdelijke pleisterplaats. We kruipen voorbij Cliché, doen Neurose en Ontzetting aan, struikelen over Gewoonte terwijl we ons langzaam en geduldig – sporen in het landschap helpen ons de juiste weg te herkennen – een weg het onspectaculaire binnenland in banen, waar Begrip, Extase en Overgave liggen te wachten. Waarom zo metaforisch? Omdat bij een boek waarin intellect en emotie elkaar in zo’n complexe choreografie ontmoeten, het begrip alleen op metafysisch niveau kan ontstaan.

Hoe dit boek te lezen? Van voor naar achter, bijvoorbeeld. In één ruk, misschien – hoewel een tegenargument kan zijn dat de romance zo lang mogelijk gerekt moet worden – , meerdere keren, dat is onvermijdelijk. Waar te starten met de duiding van dit objet d’amour? Zomaar een idee: WE BEGINNEN BIJ DE LIEFDE voor een grensland vol pracht, drama en absurditeit. De fotograaf-bewonderaar – hij maakt zijn foto’s van op afstand, alsof hij niet aan de overrompeling wil toegeven – transformeert gaandeweg van buitenstaander naar ingewijde. Onherroepelijk verandert zijn blik mee, wordt die bijgestuurd, gekleurd.

Liefde blijkt uit de manier waarop het boek is vormgegeven en uitgevoerd. Het roze van intieme dingen. De sensuele dimensie van de kattentongen-ruwe lichterroze linnen rug, dat voorhoofd (om een zoen op te drukken) en die wang (om de jouwe tegenaan te vleien). En ja, ook het roze van de verliefdheid die de kiem van dit boek vormde en de kleur van de brillenglazen waar eigenlijk heel het leven doorheen bekeken zou moeten worden.

Liefde ook van de fotograaf voor zijn tweede thuisland dat hij met de onbevangen blik van een jongeling streelt. De dansende krullen, de ontblootte billen, een godin op een steen, warme kiezels onder een handdoek, vier volmaakte perziken op een schaal, de gewelfde lippen van een vreemdeling, hypnotiserend geel, gras dat kietelt en fluisterende bomen. Maar vooral: de liefde tussen Anastasiia en haar Christian. Een zinnelijke, jaloersmakende liefde waarin de protagonisten elkaar tot poëtische hoogtes stuwen in een samentaal – een kenmerk van goede liefde.

“No. I imagine you in Koktebel learning to play durak. Or, no, in a scary garage under a grey sky in the rain when we were searching for the flying house on one leg! All I feel now is love in every cell, in every drop of my blood! I’d love to appear on your couch now, covered in salt and some lemon juice maybe, we would have a shower of tequila and dance.”

![]()

De liefde is zowel onderwerp als voertuig. Het is de liefde die een perspectief op het onderwerp Oekraïne biedt dat dichter bij een waarheid op menselijk niveau komt dan de spektakelbeelden uit de media die ons ongenadig achtervolgen. Ze komt ook tot uitdrukking in de innige relatie tussen tekst en beeld: hier trefzeker, daar weifelend, soms conflicterend. Ze ontluikt in de dialoog tussen twee fysiek van elkaar gescheiden geliefden die te midden van verandering een fundament voor hun samenzijn proberen te leggen, terwijl ze simultaan grip proberen te krijgen op het zelf in relatie tot de ander, terwijl onbegrip en verwijdering op de loer liggen.

De liefde is een psychose, een hardnekkig vasthouden aan een droombeeld dat al lang door de werkelijkheid is ingehaald; een droom die aanvankelijk al het andere naar de achtergrond verdrijft en zelfs vervangt door een eigen realiteit met het uitnodigende karakter van een ménage à trois.

Deze atlas stelt je in staat een reis te maken van buiten naar binnen, van West naar Oost en weer terug, een reis van het ene perspectief naar het andere, en van zachtheid via verwarring en irritatie naar begrijpend voelen. Het is een lange tocht, heen en weer, zonder duidelijke bestemming en met verlangen als tijdelijke pleisterplaats. We kruipen voorbij Cliché, doen Neurose en Ontzetting aan, struikelen over Gewoonte terwijl we ons langzaam en geduldig – sporen in het landschap helpen ons de juiste weg te herkennen – een weg het onspectaculaire binnenland in banen, waar Begrip, Extase en Overgave liggen te wachten. Waarom zo metaforisch? Omdat bij een boek waarin intellect en emotie elkaar in zo’n complexe choreografie ontmoeten, het begrip alleen op metafysisch niveau kan ontstaan.

Hoe dit boek te lezen? Van voor naar achter, bijvoorbeeld. In één ruk, misschien – hoewel een tegenargument kan zijn dat de romance zo lang mogelijk gerekt moet worden – , meerdere keren, dat is onvermijdelijk. Waar te starten met de duiding van dit objet d’amour? Zomaar een idee: WE BEGINNEN BIJ DE LIEFDE voor een grensland vol pracht, drama en absurditeit. De fotograaf-bewonderaar – hij maakt zijn foto’s van op afstand, alsof hij niet aan de overrompeling wil toegeven – transformeert gaandeweg van buitenstaander naar ingewijde. Onherroepelijk verandert zijn blik mee, wordt die bijgestuurd, gekleurd.

Liefde blijkt uit de manier waarop het boek is vormgegeven en uitgevoerd. Het roze van intieme dingen. De sensuele dimensie van de kattentongen-ruwe lichterroze linnen rug, dat voorhoofd (om een zoen op te drukken) en die wang (om de jouwe tegenaan te vleien). En ja, ook het roze van de verliefdheid die de kiem van dit boek vormde en de kleur van de brillenglazen waar eigenlijk heel het leven doorheen bekeken zou moeten worden.

Liefde ook van de fotograaf voor zijn tweede thuisland dat hij met de onbevangen blik van een jongeling streelt. De dansende krullen, de ontblootte billen, een godin op een steen, warme kiezels onder een handdoek, vier volmaakte perziken op een schaal, de gewelfde lippen van een vreemdeling, hypnotiserend geel, gras dat kietelt en fluisterende bomen. Maar vooral: de liefde tussen Anastasiia en haar Christian. Een zinnelijke, jaloersmakende liefde waarin de protagonisten elkaar tot poëtische hoogtes stuwen in een samentaal – een kenmerk van goede liefde.

“No. I imagine you in Koktebel learning to play durak. Or, no, in a scary garage under a grey sky in the rain when we were searching for the flying house on one leg! All I feel now is love in every cell, in every drop of my blood! I’d love to appear on your couch now, covered in salt and some lemon juice maybe, we would have a shower of tequila and dance.”

De liefde is zowel onderwerp als voertuig. Het is de liefde die een perspectief op het onderwerp Oekraïne biedt dat dichter bij een waarheid op menselijk niveau komt dan de spektakelbeelden uit de media die ons ongenadig achtervolgen. Ze komt ook tot uitdrukking in de innige relatie tussen tekst en beeld: hier trefzeker, daar weifelend, soms conflicterend. Ze ontluikt in de dialoog tussen twee fysiek van elkaar gescheiden geliefden die te midden van verandering een fundament voor hun samenzijn proberen te leggen, terwijl ze simultaan grip proberen te krijgen op het zelf in relatie tot de ander, terwijl onbegrip en verwijdering op de loer liggen.

De liefde is een psychose, een hardnekkig vasthouden aan een droombeeld dat al lang door de werkelijkheid is ingehaald; een droom die aanvankelijk al het andere naar de achtergrond verdrijft en zelfs vervangt door een eigen realiteit met het uitnodigende karakter van een ménage à trois.

“News on radio: they put love diagnosis to the world list of mental diseases…”

BUITEN DE COCON DAVERT DE ACTUALITEIT. Terwijl de ontdekkingsreis vordert, de verzengende liefde een gematigder temperatuur krijgt en het winter wordt, manifesteren de gebeurtenissen zich hoe langer hoe meer in de berichten. Hoop is nodig, ondanks de vreemdeling op het bankje die wijst op onwaarschijnlijke gebeurtenissen uit het verleden. We moeten blijven geloven in de kracht van liefde, de kracht die je een beter mens doet worden, de kracht waarop een land zichzelf kan doen verrijzen en haar stof en ballast kan afschudden.

“We are drinking a milkshake that tastes like lipstick from an old pleasure madam who sticks her nose in dusty books to get high; but reality is to absurd and grotesque to sink in pages!”

Het hele boek lang speelt het spektakel op het tweede plan. De politieke gebeurtenissen lijken zodoende buiten de foto plaats te vinden. Ze verstoppen zich in en tussen sporen die slechts door de geduldigen gelezen kunnen worden, in plaatsen en lichamen waarvan de betekenis zich enkel prijsgeeft door een minutieus verkennen van details, ook de schijnbaar onbeduidende, omdat die net zoveel zeggen als de schreeuwerige. Alleen in rust ontvouwt zich de rest van het karakter. Te weten waar en wanneer we precies zijn, wiens bloed of welk roet wordt weggepoetst, welke deals worden gesloten en welke leuzen onleesbaar gemaakt is van ondergeschikt belang. “Da Pravda!”, schrijft onze hoofdpersoon, de waarheid is echter subjectief en pluriform.

![]()

Eén waarheid is dat er naast de actualiteit van tumult en bominslagen ook het dagelijks leven is, dat de koelkast gevuld moet worden, de zon altijd en overal ruggen verwarmt; de warmte van een eindeloos lijkende zomer die zich alleen laat verjagen door een koele duik. En in elke actualiteit is er is altijd ook de liefde. Het boek staat bol van dergelijke tegenstellingen – Christian versus Anastasiia, oude versus nieuwe overtuigingen. Welk – en wiens – Oekraïne we krijgen voorgeschoteld is een onmogelijk te beantwoorden vraag. Daarbij, het is onzin om te streven naar een antwoord als er nog gezocht wordt, onderwijl in de wetenschap verkerend dat er alleen fragmenten gevonden zullen worden.

TERUG NAAR HET BEGIN. De fotografie heeft steeds een relatie tot tijd en plaats, maar binnen de grenzen van dit boek, deze roze cocon, vormt ze haar eigen universum dat op geen enkele kaart te vinden is. Dit boek is de atlas van een poëtisch land waarin de schilferende verf van een betonnen zwembad de bast van een plataan imiteert en de omgewoelde aarde rond de stam van diezelfde boom op haar beurt zich aan de vorm van het zwembad spiegelt. Het is ook een land van wensen, dromen en mogelijkheden, zoals nieuwe naties die geboren worden uit de dromen en speeches met het doel verandering te brengen (en worden omgebracht omdat de niet gedroomde wereld bang is voor wat zou kunnen zijn).

Terug naar die ongelofelijke titel, ontleend aan het werk van de schrijver Joseph Brodsky. Herinneringen als valscherm voor een veilige landing in het heden of de toekomst. Herinneringen als drijfhout die ons, door ze te delen, helpen onthouden dat we niet gek zijn, terwijl we al dobberend ook nieuwe herinneringen maken. Dat geldt zowel de liefdesrelatie als de zoektocht van een land naar een eigen culturele identiteit.

Is het mogelijk nostalgisch te zijn naar een plek waar we nooit zijn geweest? Wel als die besloten ligt in een boek dat even fysiek is als de realiteit. Bij het elke volgende keer openslaan zal de betekenis van wat zich op de pagina’s bevindt veranderd zijn, zoals tijd ook de facetten van een geliefde prijsgeeft. Zelfs die gestolde vorm is niet voor altijd vast.

BUITEN DE COCON DAVERT DE ACTUALITEIT. Terwijl de ontdekkingsreis vordert, de verzengende liefde een gematigder temperatuur krijgt en het winter wordt, manifesteren de gebeurtenissen zich hoe langer hoe meer in de berichten. Hoop is nodig, ondanks de vreemdeling op het bankje die wijst op onwaarschijnlijke gebeurtenissen uit het verleden. We moeten blijven geloven in de kracht van liefde, de kracht die je een beter mens doet worden, de kracht waarop een land zichzelf kan doen verrijzen en haar stof en ballast kan afschudden.

“We are drinking a milkshake that tastes like lipstick from an old pleasure madam who sticks her nose in dusty books to get high; but reality is to absurd and grotesque to sink in pages!”

Het hele boek lang speelt het spektakel op het tweede plan. De politieke gebeurtenissen lijken zodoende buiten de foto plaats te vinden. Ze verstoppen zich in en tussen sporen die slechts door de geduldigen gelezen kunnen worden, in plaatsen en lichamen waarvan de betekenis zich enkel prijsgeeft door een minutieus verkennen van details, ook de schijnbaar onbeduidende, omdat die net zoveel zeggen als de schreeuwerige. Alleen in rust ontvouwt zich de rest van het karakter. Te weten waar en wanneer we precies zijn, wiens bloed of welk roet wordt weggepoetst, welke deals worden gesloten en welke leuzen onleesbaar gemaakt is van ondergeschikt belang. “Da Pravda!”, schrijft onze hoofdpersoon, de waarheid is echter subjectief en pluriform.

Eén waarheid is dat er naast de actualiteit van tumult en bominslagen ook het dagelijks leven is, dat de koelkast gevuld moet worden, de zon altijd en overal ruggen verwarmt; de warmte van een eindeloos lijkende zomer die zich alleen laat verjagen door een koele duik. En in elke actualiteit is er is altijd ook de liefde. Het boek staat bol van dergelijke tegenstellingen – Christian versus Anastasiia, oude versus nieuwe overtuigingen. Welk – en wiens – Oekraïne we krijgen voorgeschoteld is een onmogelijk te beantwoorden vraag. Daarbij, het is onzin om te streven naar een antwoord als er nog gezocht wordt, onderwijl in de wetenschap verkerend dat er alleen fragmenten gevonden zullen worden.

TERUG NAAR HET BEGIN. De fotografie heeft steeds een relatie tot tijd en plaats, maar binnen de grenzen van dit boek, deze roze cocon, vormt ze haar eigen universum dat op geen enkele kaart te vinden is. Dit boek is de atlas van een poëtisch land waarin de schilferende verf van een betonnen zwembad de bast van een plataan imiteert en de omgewoelde aarde rond de stam van diezelfde boom op haar beurt zich aan de vorm van het zwembad spiegelt. Het is ook een land van wensen, dromen en mogelijkheden, zoals nieuwe naties die geboren worden uit de dromen en speeches met het doel verandering te brengen (en worden omgebracht omdat de niet gedroomde wereld bang is voor wat zou kunnen zijn).

Terug naar die ongelofelijke titel, ontleend aan het werk van de schrijver Joseph Brodsky. Herinneringen als valscherm voor een veilige landing in het heden of de toekomst. Herinneringen als drijfhout die ons, door ze te delen, helpen onthouden dat we niet gek zijn, terwijl we al dobberend ook nieuwe herinneringen maken. Dat geldt zowel de liefdesrelatie als de zoektocht van een land naar een eigen culturele identiteit.

Is het mogelijk nostalgisch te zijn naar een plek waar we nooit zijn geweest? Wel als die besloten ligt in een boek dat even fysiek is als de realiteit. Bij het elke volgende keer openslaan zal de betekenis van wat zich op de pagina’s bevindt veranderd zijn, zoals tijd ook de facetten van een geliefde prijsgeeft. Zelfs die gestolde vorm is niet voor altijd vast.

De tien mooiste Nederlandse fotoboeken 2018

volgens de Volkskrant-redactie

Opgegraven mobieltjes, een verafschuwde vogel en gereformeerde gelukszoekers.

De Volkskrant koos de mooiste 10 Nederlandse fotoboeken van 2018. Mark Moorman, Merel Bem en Arno Haijtema

De Volkskrant koos de mooiste 10 Nederlandse fotoboeken van 2018. Mark Moorman, Merel Bem en Arno Haijtema